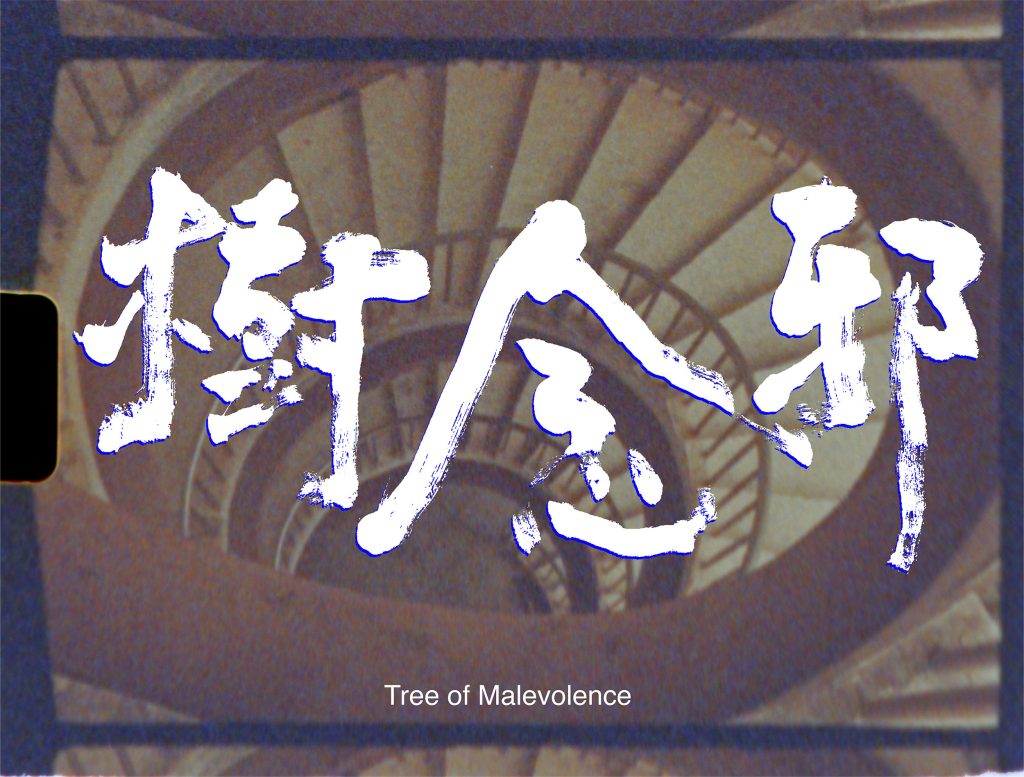

Exhibition Review:

Tree of Malevolence: The aesthetics of geopolitical space, fragmented narratives, and the phantom

by Yining He

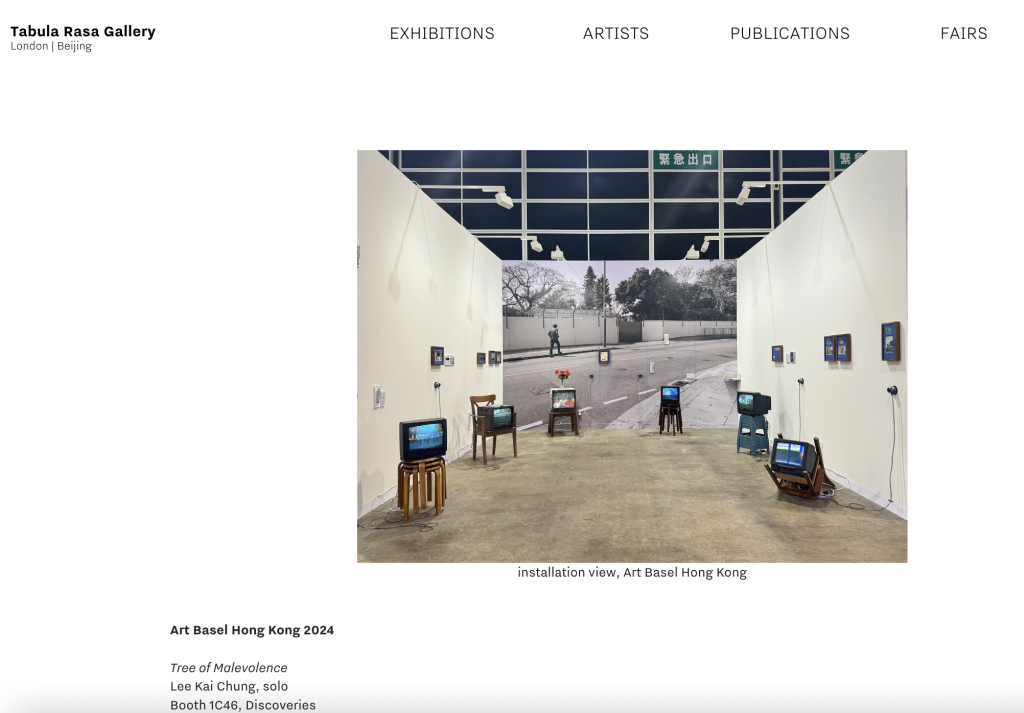

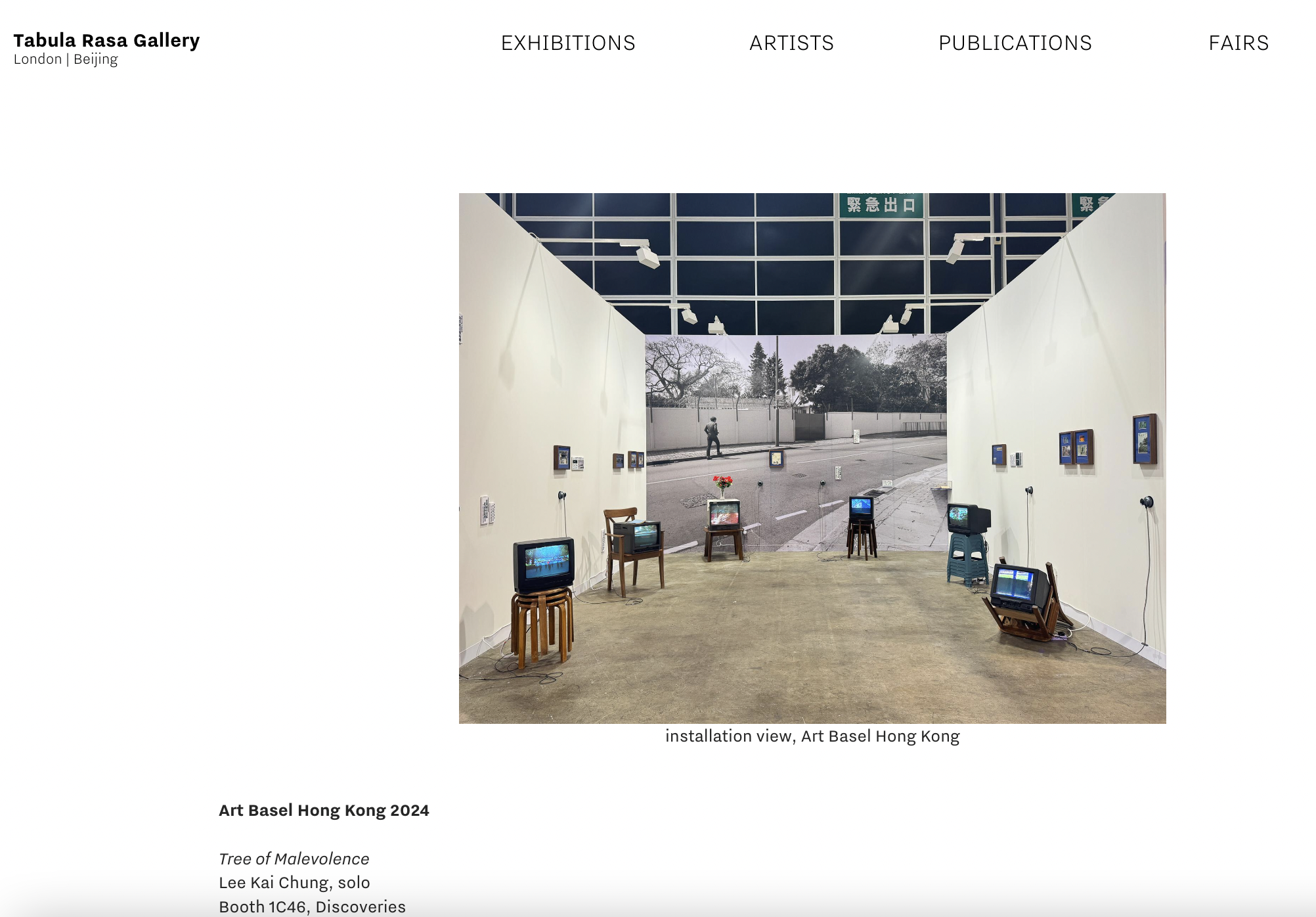

Art Basel Hong Kong 2024

Tree of Malevolence

Lee Kai Chung, solo

Booth 1C46, Discoveries

Lee Kai-chung, Tree of Malevolence, sextuple-channel video installation(Super 8 film transferred to digital, colour, sound), 34 min, 2024

I wander within the vast structure, a converted old barn turned sanctuary of knowledge, where staircases crisscross, linking libraries, classrooms, studios, and beyond. Each door I push ajar seems to usher me onto a distinct narrative path, wherein every step unravels threads of memory, crafting a comprehensive tale of the building’s essence. As doors swing back and forth, I sense subtle shifts in the temperature, blurring the boundaries between my physical presence and the space around me.

Contemplating the various possibilities of narrative unfolding within this space, fragmented scenes from the recent viewing of “Tree of Malevolence” resurface in my mind. Amidst the towering palm trees, a sightseeing elevator slowly ascends, seemingly about to leap out of the frame; spiraling staircases descend deep, inviting visitors on a dizzying journey through the complex tapestry of history.

In the entanglement of power dynamics and the dissemination of information, how do individuals navigate their narratives and identities to carve out survival space while preserving personal safety? To what extent does intelligence wield influence, shaping individual events, moulding the course of history, and potentially reshaping personal, regional, and national narratives? During pivotal historical epochs, how does a geographical locale intertwine with global geopolitics, thereby moulding its regional discourse? Delving into the past, how do artists’ research interests and historical perspectives unearth tales long buried in the remnants of eras gone by, subsequently unravelling the threads of historical significance and inquiry?

Furthermore, what roles do personal experiences and embodied knowledge assume in the curation, narration, and reinterpretation of historical archival materials? Within the realm of art, how do historical events act as anchor points for intricate visual narratives, and how do artists navigate the selection, processing, and reimagining of historical data and imagery? Through this approach, how does art facilitate a discourse that resonates within contemporary social and cultural contexts?

I ascended to the top level of the building’s corridor, my body still carrying the sensations of navigating through the structure. As I leaned forward to observe the architecture’s intricacies, a floor plan for the conversion of a factory into a dwelling unfolded in my mind. Alongside this visualization, the questions swirling in my thoughts grew clearer by the moment. Finding a secluded corner, I opened my laptop and returned to the interface of “Tree of Malevolence,” attempting to trace several paths for viewing and understanding the creation and narrative of the artwork.

Lee Kai-chung’s latest hexa-frequency video installation, “Tree of Malevolence,” is a research-based project rooted in the life stories of intelligence operatives during the Cold War era. Set against the backdrop of China’s Greater Bay Area, the artwork showcases the artist’s unique appropriation and innovative reconstruction of personal narratives, historical events, and archival materials. Through personalized storytelling, Lee Kai-chung examines the intricate interplay between information circulation, political discourse, and spatial layout during the Cold War, thereby unveiling t the nuanced dimensions of individual agency and human behaviour under the influence of collectivism.

The inspiration for “Tree of Malevolence” stemmed from Lee Kai-chung’s in-depth interview with an elderly woman in Hong Kong in 2018. During this encounter, the woman shared poignant anecdotes about her mother’s involvement in intelligence activities during the tumultuous 1950s. This narrative sparked Lee Kai-chung’s curiosity and ignited his creative inspiration. Drawing not only from the elderly woman’s account but also from meticulous research and verification of individuals, events, and historical archives, the artist embarked on a multifaceted exploration.

Based on the script created around the clues of the elderly woman’s mother’s involvement in intelligence work and the trajectory of her personal life, Lee Kai-chung then crafted six independent video segments by combining the archival images he collected and selected with the materials accumulated from his field shooting in the Greater Bay Area. Each segment, approximately six minutes in length, serves as a standalone narrative, yet they ingeniously interweave to form a cohesive visual and narrative symphony. They converge to create a complex narrative maze, guiding the audience through the perspective of the narrator Y into a world meticulously pieced together from historical fragments.

The historical context depicted in “Tree of Malevolence” can be traced back to the Japanese invasion of Hong Kong in 1941. Taking advantage of the opportunity when Britain once considered using the Communist Party of China’s forces to restrain the Japanese from advancing into Hong Kong, the clandestine liaison network pre-established by Communist revolutionaries in Hong Kong aimed to establish “direct radio communication with Yan’an for intelligence exchange.”[1] During the Japanese occupation period, along with the establishment of the Eighth Route Army’s office in Hong Kong in 1938, the covert frontline in Hong Kong served as an important base for the anti-Japanese movement, responsible for receiving donations from Hong Kong, Macau, and overseas, transporting strategic materials, and rescuing revolutionary and cultural figures in Hong Kong.[2]

The power dynamics on Hong Kong Island underwent a significant shift with the Japanese occupation in August 1943, transforming the island into a bustling hub for various intelligence agencies during World War II. Here, the United States, Britain, Japan, and their respective intelligence agencies converged, navigating a delicate balance of power relations. This complex geopolitical landscape persisted into the Cold War era, where Hong Kong, owing to its geographical remoteness from the centres of the United States and the Soviet Union, and its unique historical position, presented new avenues for the realization of imperialist ideals amid the Cold War backdrop.[3]

Throughout the Cold War period, Hong Kong, with its rapidly burgeoning capitalist economy, stood juxtaposed against Guangzhou, implementing a socialist economic model and serving as a crucial gateway for external exchanges due to its strategic geographical location. The Canton Fair of 1957, a prominent centre for foreign trade, thrived on the flow of intelligence information traversing both sides of the Hong Kong River. In the intricate interplay between the capitalist and socialist spheres, this bay area emerged as a nexus for resources and information exchange, thus becoming a distinctive geopolitical space in the annals of modern Chinese history.

As delineated above, spanning from the 1940s to the 1960s, the turbulent times in the Greater Bay Area provided both the historical context and spatial discourse for the artwork’s narrative. Although Lee Kai-chung’s narrative strategy usually starts with individualized storytelling to enter historical events, in “Tree of Malevolence, ” the special identity of the narrator as an intelligence officer adds a layer of complexity to the narrative. The artist intentionally deconstructs historical events such as the Canton Fair, the Keshiya Princess incident, and the Bandung Conference in this artwork, intertwining them with individual memories and narratives to create an immersive narrative scene.

Each seemingly isolated storyline is cleverly woven together, revealing the daily lives and actions of intelligence officers on the covert frontline. Here, personal, institutional, national, and spatial narratives converge, highlighting the complexity and chaos of intelligence activities and the events behind the scenes, particularly during this extraordinary period. In the artist’s creative rendition, authenticity takes a backseat, allowing the audience to delve into the obscure corners of history, and to grasp the intricate relationships entwining power struggles, political controversies, and individual survival and choices.

In Lee Kai-chung’s video art, fragments of history are deftly captured, blending the contradictions between collective and individual consciousness to construct a phantasmagorical aesthetic space. The imagery in “Tree of Malevolence” unfolds like a dream, drawing viewers into a labyrinth composed of rough footage from different historical periods, along with prominent grainy Super 8 film material. The viewer’s gaze, accompanied by the camera’s jitter, shifts through architectural structures and monuments laden with geopolitical symbolism, lush vegetation, and wandering streets, as if these visuals stir echoes from the depths of the subconscious.

Images such as the metamorphosed portrayal of the Bandung Conference, steeped in historical metaphors, resemble a mist of simultaneous light, inviting contemplation. On those nostalgic playback devices, these images intertwine with the narrative in the script, weaving through history and reality like threads on a loom, revealing a fleeting, elusive beauty imbued with a hint of mystery. The identities and actions of intelligence officers, like ghosts of the times, progress through the artist’s swaying cinematic language, rapid editing techniques, and dream-like visual expressions, driving the originally fragmented narratives to reflect upon each other visually, becoming mirrors within mirrors.

As daylight dims, the building’s interior is shrouded in darkness. From the outside, its square structure appears so straightforward, in stark contrast to the perspective from within. Watching “Tree of Malevolence” feels akin to venturing into this enigmatic space; Lee Kai-chung weaves scattered historical fragments into a richly layered narrative network, thereby exploring the complexity of history, uncovering obscured individual experiences, and offering profound insights into the artist’s historical perspectives. Every grainy, jittery moment in the footage becomes an entry point for deconstructing grand historical narratives, leading us into those often overlooked personal stories and subtle geopolitics.

Lee Kai-chung’s artwork reminds us that history is not a singular linear narrative but a rich tapestry woven from countless individual experiences and choices. In this world, the forgotten individuals and their convoluted stories, presented by the artist with an almost mystical passion, invite viewers to delve deeper into ways of engaging in dialogue with history and to reflect on the roles played by individuals within it.

References

[1] Prasenjit Duara (2009). Hong Kong and the New Imperialism in East Asia, 1941-1966. In Colonialisms and Chinese Localities (pp. 159-182). Beijing: People’s Publishing House.

[2] Party History Materials of the Southern Bureau, Volume Three. (1986). Chongqing: Chongqing Press.

[3] Yang Qi (2014). The Great Rescue of Hong Kong during the Occupation. Hong Kong: Joint Publishing.

Reply